I watched an interesting video describing the fact that pests don’t feed on healthy plants. How do you measure plant health? Simple. Just take a Brix reading.

Around the same time I became aware of the fact that spraying molasses on plants not only increases Brix values but also creates healthier plants with fewer pests. This has become a very popular technique among dahlia growers and seems to have some support from gardeners.

Let’s dig into the connection between Brix, molasses and pests.

This post uses affiliate links

What is Brix?

I have discussed this in detail in another post but to summarize, brix is an indirect measure of the amount of solute (chemicals) in a liquid sample. Since plant sap contains mostly sugar, the brix reading correlates quite closely with the amount of sugar in the sap.

The brix reading can be taken from various parts of a plant including leaves, fruits, seeds and roots. Each part will have a different brix value. The discussion in this post deals only with leaf Brix.

Claims for Brix, Molasses and Pests

There are numerous claims but I have decided to focus on these key ones:

- Healthy plants do not have insect pests.

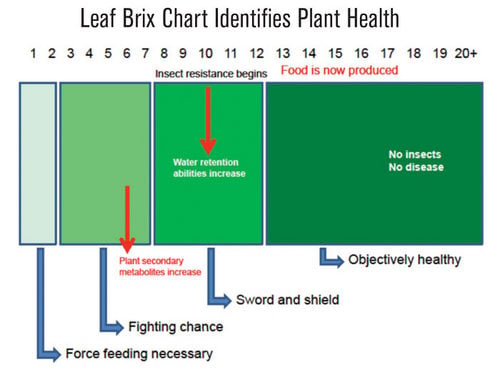

- A plant is only healthy if it has a Brix above 12.

- Spraying plants with molasses will increase their Brix reading.

- GMO plants can’t attain a Brix of 12 and therefore are never healthy.

The genesis for this post was a video by Dr. Tom Dykstra. In it he claims that healthy plants have a Brix above 12 and that such plants are always pest free. He also claims that GMO plants are unable to attain a Brix of 12 and therefore they are never healthy.

Unfortunately the video did not provide any references to support the claims so I contacted Dr. Dykstra to get some. He was kind enough to respond and told me, “I am not allowed to publish (due to confidentiality agreements), so I know there are no references from me. I am not aware of any studies that have been undertaken or funded to analyze the question of Insects and Brix. So, outside of the article I briefly mentioned at the end of the video, during the Q&A, there are none”. He goes on to say, “I am not aware of any studies that have been undertaken or funded to analyze the question of Insects and Brix”.

The above mentioned video was sponsored by the Soil Food Web School, and similar videos have been produced by other regenerative agricultural groups. None of the videos I watched provided supporting evidence for their claims.

I hope you are asking yourself, how can anyone make claims about Brix and insects when there are no supporting studies? It is certainly the question I asked.

What is a Healthy Plant?

The term healthy plant is used a lot in gardening circles and there are many descriptions of unhealthy plants, but I could not find any accepted definition for the term “healthy plant”.

Some basic chemistry will provide a better understanding of the term. Plants use photosynthesis to collect light energy and combine that with carbon, from CO2, to form sugar. Sugar provides two key elements for life: carbon and energy.

Carbon is a key component of just about every chemical found in a plant. It is no exaggeration to say that a plant is mostly carbon (and oxygen). Nothing happens in a plant without enough carbon.

The second key component to life is energy and almost all life forms use sugar as an energy source. This energy is required for almost every chemical reaction in a plant and it is so critical that without it, plants die.

Sugar is used to make just about everything in the plant. When it is combined with nitrogen, the plant is able to make amino acids which are key building blocks for proteins. Many proteins are enzymes which are used to carry out most chemical reactions.

Based on these fundamental facts, a healthy plant can be defined is one that can produce lots of sugar and has enough nitrogen to make amino acids. It also has adequate amounts of all of the plant nutrients because they are also essential for building plant chemicals. Using this basic knowledge let’s consider different plant conditions.

A healthy, rapidly growing plant will have a high level of photosynthesis, which produces lots of sugar. This plant will also have lots of nitrogen and other nutrients, so the sugar is quickly converted to amino acids and thousands of other compounds a plant needs to make stems, leaves and roots. The production of these chemicals and new plant parts keeps the level of sugar in leaves relatively low. As soon as some is made, it gets used by the plant. A healthy, rapidly growing plant will therefore have a lower Brix reading.

A dying plant will not be doing much photosynthesis, have a low sugar level and a low amino acid level. It’s Brix is also low.

A healthy plant that is getting ready for winter will have a high level of photosynthesis and will be making a lot of sugar. But since the plant is shutting down, this sugar is not used to make other compounds. Instead it is stockpiled. Such a plant will show a higher leaf Brix reading until late fall when it shunts all of the sugar into branches and roots.

Why is Brix important? Brix measures mostly sugar and sugar is both the build block of most of the compounds found in plants and it is the energy source for making those compounds. Since sugar is important for plant healthy it follows that Brix may be an indicator of health.

There is also a fourth kind of plant – the unbalanced plant. It does not have all of the nutrients required to convert its sugar. Its supply of nutrients is unbalanced. Provided photosynthesis is still active, the sugar produced piles up in the leaf and results in a high Brix reading. To visualize this, consider an automobile assembly line that has run out of steering wheels? It can’t produce finished cars, but half-built cares start piling up. In the same way sugar piles up in the plant.

Let’s summarize the above plant conditions:

- A healthy growing plant has a low Brix.

- A dying plant has a very low Brix.

- A healthy plant going into dormancy has a high Brix.

- An unbalanced plant has a high Brix.

This does not define a healthy plant, but it does illustrate that Brix is not a measure of healthiness.

Chaboussou (see below) defined a healthy plant as one that is in metabolic balance. It is growing well for its current state (dormant or growing) and is photosynthesizing enough to meet its needs. He went on to state that, it may or may not have a higher Brix reading.

This contradicts what Dr. Dykstra and some other fringe groups claim, namely that a plant is only healthy if it has a Brix above 12.

The idea that a plant is only healthy when it has a high Brix does not make sense given what we know about plant chemistry and growth. There is also no supporting science that supports such a claim.

Pests Don’t Feed on Healthy Plants

This seems like a fantastical claim. Don’t we all grow healthy plants? Does agriculture not grow healthy crops? And yet most of these plants have pests.

Why Do Insects Eat Plants?

Insects need food just like every other organism. They eat plants that provide the nutrition they need.

You might think that a grasshopper will eat anything that is green but they are more selective than most gardeners realize. They need two main things from their diet. Their food needs to have the right amount of nutrients to keep them healthy and have to be able to digest the food. The two most important nutrients are sugar and amino acids for nitrogen.

Insects tend to leave unhealthy plants alone because they don’t provide enough nutrients. Plants going into dormancy might be a good sugar source but they are usually low on amino acids so they are also ignored. What about a healthy, rapidly growing plant? They also have low sugar levels and may not be the best choice.

The best choice for insects might be the unbalanced plants. They have a high sugar level and depending on the type of unbalance, they may also have a high nitrogen or amino acid level.

These ideas were presented by Francis Chaboussou, an agronomist of France’s National Institute of Agricultural Research (INRA), in a book called Healthy Crops: A New Agricultural Revolution (1985) where he describes this phenomena called the trophobiosis theory. You can get a free copy of Healthy Crops: A New Agricultural Revolution here.

Trophobiosis theory has been characterized by Jose Lutzenberger, as “a pest starves on a healthy plant” (1995). Proponents of this theory, which include organic and regenerative agricultural groups, believe that the goal should be to grow healthy plants and the pests and diseases will no longer be a problem.

Dr. Philip Callahan of the University of Florida has added some fuel to this theory. He found that insects can detect signals from plants which allow them to determine if a plant meets its dietary needs. He said, “If a plant is in perfect or near perfect health (mineral balance), it will vibrate at a given composite frequency. If there happens to be a mineral deficiency, it will vibrate at a slightly different composite frequency. If there is a serious deficiency or several deficiencies that make that plant unfit for animal or human consumption, it will vibrate at a significantly different frequency that the insects know as food, hence an insect infestation”. Dr, Callahan is also the author of the book, Paramagnetism: Rediscovering Nature’s Secret Force of Growth.

Although Dr. Callahan’s description of “composite frequency” may not be right, the basic concept is valid. Insects do have an ability to evaluate a plants suitability as a food source.

Scientific Support for Trophobiosis

As mentioned above healthy plants, dying plants and dormant plants are not good candidates as food for insects. Unbalanced plants are a better food source.

The plant may be missing some key nutrients that are preventing the formation of enough proteins. That causes the plant to build up amino acids – candy to a pest. Sudden extremes in the environment (temperature, moisture) can also cause this.

The gardener can also cause an unbalanced condition. Too much nitrogen fertilizer can build up excess nitrogen and amino acids in the plant sap. Pesticides can disrupt the biochemistry of the plant as well.

“Recent metabolomic analyses demonstrate that exposure of crops to pesticides can result in subtle metabolic disruption and, consequently, in accumulation of nutritionally valuable amino acids within crop tissues. This effect may not be sufficient to cause visible signs of toxicity or stress in the plant, and thus it may go unnoticed by growers in the field”.

There is quite a bit of knowledge that indicates pests can make good selections for their meals and that they tend to feast on unbalanced plants. In many cases these unbalanced plants look quite normal and healthy to a gardener.

Do Pests Only Feed on Unhealthy Plants?

Some claims state this very categorically; pests will not feed on healthy plants. When science measures pests in fields, they are found on unbalanced plants as well as healthy plants. However, the numbers tend to be higher on unbalanced plants.

Insects do seem to prefer unhealthy/unbalanced plants, but that does not mean they won’t eat healthy plants.

Does high Brix indicate such “unbalanced” plants? Unbalanced plants may have higher Brix if sugars are building up, but that will depend on the actual cause for the imbalance. It is also quite possible that an unbalanced plant has a low Brix.

Except for the above mentioned video by Dr. Dykstra and online references to him, none of the other references mention Brix. Although there is some support for the trophobiosis theory, there seems to be little support for the use of Brix measurements to identify food sources for pests.

So do pests only feed on unbalanced plants? No. If pests need to eat they will eat the plants that are within reach. They may prefer certain plants over others for a number of reasons including the nutrition in the plant sap, but none of the reliable sources of information claim that it is an all or nothing thing.

High Brix is Not Toxic

One argument as to why insects don’t feed on plants with high brix is that they can’t digest the high sugar levels – they are toxic to insects.

Testing with aphids has shown that they are quite happy ingesting solutions with a Brix of 34, far above the magic 12 reading. Even at 34 Brix, the food is not toxic.

Do Insects Feed on High Brix Plants?

Let’s ignore the complication of defining “healthy” and ask a different question. Is there a relationship between insect feeding and Brix level?

Even though this claim is made a lot, there is very little scientific data on this. A review by Lena Syrovy and Renee Prasad in 2010 found only 4 studies that looked at the relationship between plant Brix levels and insect feeding.

A very extensive study testing grapevines in five organic and three conventional farms over two years found no general relationship between leaf Brix readings and insect herbivory. Leafhopper numbers actually went up with higher Brix on some sites. They concluded, “results compiled during this rigorous two-year empirical study provides no consistent support for the alleged predictive Brix / leafhopper relationship as it has been widely promoted in recent years”.

Similar results were found for aphids on potato plants.

Another study concluded that, “Brix refractometry was not an applicable method to use for determining resistant sorghums to sugarcane aphids.

- There seems to be no scientific support for the claim that insects don’t feed on high Brix plants.

- Brix is not a suitable measurement to predict insect herbivory.

- There is no support for the magic Brix number 12.

Does Molasses Increase Brix?

Gardeners seem to love spreading molasses around the garden. Those who buy into the idea that a high Brix will prevent pests seem to be more inclined to believe molasses will prevent pests. Why is that? Molasses is mostly sugar and water. Adding sugar to plants should increase Brix.

In one study spraying 5 or 20% sucrose solutions on noni plants produced higher yields.

A study was conducted by researchers in Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, and Indiana in 2010 comparing different sources of sugar (including molasses) and an untreated check in soybeans. There was no increase in yield.

In another study neither dextrose nor sucrose increased yields in corn or soybean.

I don’t know if the Brix leaf value increases after spraying with sugar or molasses, but it may go up a bit. What does seem to be clear is that spray sugar or molasses has limited effect on yield and therefore it probably has a limited effect on plant growth.

Spraying Dahlias With Molasses

For some reason this has become a hot topic for dahlia growers. Anecdotal evidence (i.e. peoples opinions) suggests that it produces stronger plants and may keep pests away.

I decided to join a dahlia Facebook group that has quite a few posts on this subject and then I asked for some references to support the idea. I got none. Then I asked for results from people who tried spraying molasses and had a control. I got none. A search in Google Scholar turned up nothing.

Spraying molasses on dahlias seems like wishful thinking!

GMO Plants Always Have Pests

Dr. Dykstra also makes this claim. GMO plants are never healthy and therefore they always have pests. He defines healthy as Brix over 12. So the claim can be restated as GMO plants always have Brix values that are lower than the similar non-GMO variety.

I specifically asked for proof of this but Dr. Dykstra had none. I checked for references that looked at Brix levels in GMO and non-GMO plants and found none.

Most GMO modifications have nothing to do with photosynthesis or the production of amino acids. Therefore it is very unlikely they have any effect on Brix. This seems to be just another hollow anti-GMO claim.

Conclusion About Brix, Molasses and Pests

- The claim: healthy plants do not have insect pests. Not true. But pests prefer unbalanced plants which may look perfectly healthy to a gardener, at least in the early stages of unhealthiness.

- The claim: a plant is only healthy if it has a Brix above 12. There is no scientific support for this claim.

- The claim: spraying plants with molasses will increase their Brix reading. This may be true, but the increase is so small it does not grow better plants and it is unlikely to deter pests.

- The claim: GMO plants can’t attain a Brix of 12 and therefore are never healthy. No scientific support for this claim.

There is little scientific support for spraying molasses on plants like dahlias to make them grow better or to reduce pests.

Healthy growing plants are likely to have fewer pests than plants that are unbalanced, but the idea that a healthy plant has no pests is not true. The distinction between these two categories of plants can be hard for a gardener to determine. The problem is easier to see as plants become more unbalanced and less healthy over time.

Brix is a very crude way of measuring plant status and is not a reliable way to evaluate the overall health of a plant.

Best advice for gardeners – don’t follow such fringe suggestions.

Kudos, once again, for systematically dismantling a popular misconception. Gardeners have enough to worry about without the distraction of disinformation. I bought a brix meter after watching this video and have been feeling guilty about not putting it to use! Thanks to you, one less distraction. Is there any legitimate use for this tool in gardening?

Good article. But like so many common practices that people use and with success, the fact remains that if the hypothesis behind a study will not result in a product that can be patented, then it will not likely be done. So, many traditional beneficial practices will never never be “proven”.

If pests don’t eat healthy plants, why have my (very healthy) brassicas suffered severe damage from caterpillars?

Strangely enough, those under netting haven’t suffered in the same way but slugs have, as ever, been a nuisance to deal with.

I make wine, and a brix of 12 suggests that the sap has 12% of the liquid as equivalent to sugar. Fully ripe fruit (other than wine grapes) might have juice with 12% sugar, but leaf and stem of plants? A brix of 12 is equivalent to a specific gravity (density) of about 1.048. And that is equivalent to dissolving slightly more than 1 lb of sucrose in water to make 1 US gallon. I would be gobsmacked to think that just about every plant contains the equivalent of that ratio of sugar to water in leaf and stem